"They believed what I was doing was a benefit to all in aviation."

Membership in EAA was open to anyone having an interest in the common purpose of the organization and homebuilt aircraft, regardless of race or sex or anything else. Membership cards were introduced, and the constitution and its bylaws were written and approved. Paul brought in famous aviation personalities such as Frank Tallman and Steve Wittman to speak to the group. Together, he and Audrey began to self-publish a monthly newsletter called The Experimenter for EAA members.

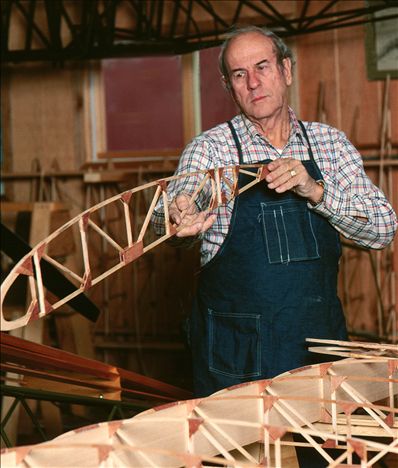

FLYING magazine, the largest circulation aviation monthly at the time, published a letter to the editor written by Paul outlying his desire to see a revitalization of the homebuilt movement that had its beginnings in the 1920s. National interest in homebuilt airplanes began to kindle.

In September of 1953, the EAA hosted its first official fly-in with 22 aircraft and fewer than 150 people in attendance. "We were amateurs! Audrey and I could be found scurrying all over the airport, parking airplanes, greeting pilots, running to the pay station, trying to find motel accommodations and, in some cases, helping to solve and fix maintenance problems," Paul said.

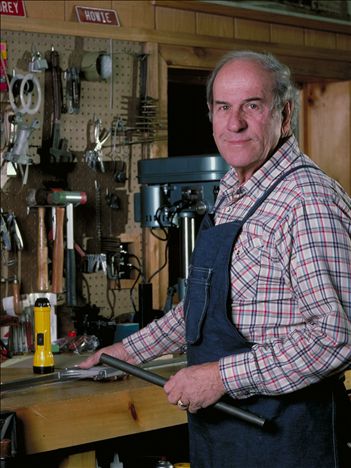

In 1954, Mechanix Illustrated magazine ran a feature article about Paul and the Baby Ace aircraft he had built. The article told readers that building and flying your own airplane was possible, and affordable. Within three days of publication, Paul received 126 letters asking for more information about EAA. By the time EAA hosted its second fly-in, the organization could claim more than 200 card-carrying members, and 700 people watched the show. Soon after, EAA began its "Teen-Hi Airlift" (the precursor to the Young Eagles) and gave first rides to more than 1,500 teenagers in hopes of spurring their interest in aviation. (The Young Eagles program has given more than 1.8 million airplane rides.)

Despite the time requirements of his full-time job with the Wisconsin Air National Guard, Paul did his best to personally respond to everyone who took interest in the group.

"As the EAA began to attract more and more interest, it became increasingly difficult for me to keep up with all the correspondence and other activities. If it hadn't been for Audrey, I wouldn't have been able to handle it. Fortunately I also had her support and the support of my Air Guard unit. They believed what I was doing was a benefit to all in aviation."

Paul led EAA as a volunteer until the early '70s when he retired from the National Guard and took his first paid position with the organization.